What is a Name?

Why did your parents choose your name? In some cases, it will have been a family name or someone meaningful to them. In most cases, I would argue that your parents would just say, “well, we liked that name.” It’s likely that there were external influences being applied to your parents, unbeknownst to them, that made them like that name. Or even be aware of that name! Perhaps, they were pregnant and met a child with a name that they really liked. Or if you weren’t the first born, they could’ve easily “borrowed” your name from a toddler or infant they met at day care.

While baby names, on the surface, may not be the most interesting piece of data, there can be significant cultural influences on how parents name their children. Below, I unpack some Census data, make some inferences on collective naming psychology, and pontificate in general about how we choose names and what influences us.

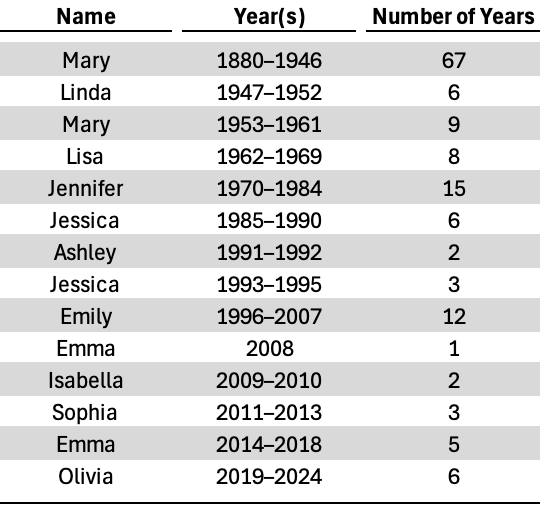

Women

Only 11 unique names have topped the list for females since 1880, with the name Mary topping the list for over half of these years. Mary is a profoundly religious name (mother of Jesus), which explains its popularity in the first part of the 20th century, specifically during times of hardship around the Great Depression and World War II. Similarly, it is unsurprising that this name has lost popularity recently to more modern names like Sophia, Emma, and Olivia.

The only thing that could dethrone the Virgin Mary, albeit briefly, was the song Linda by Buddy Clark, which sparked a massive surge in the name Linda.

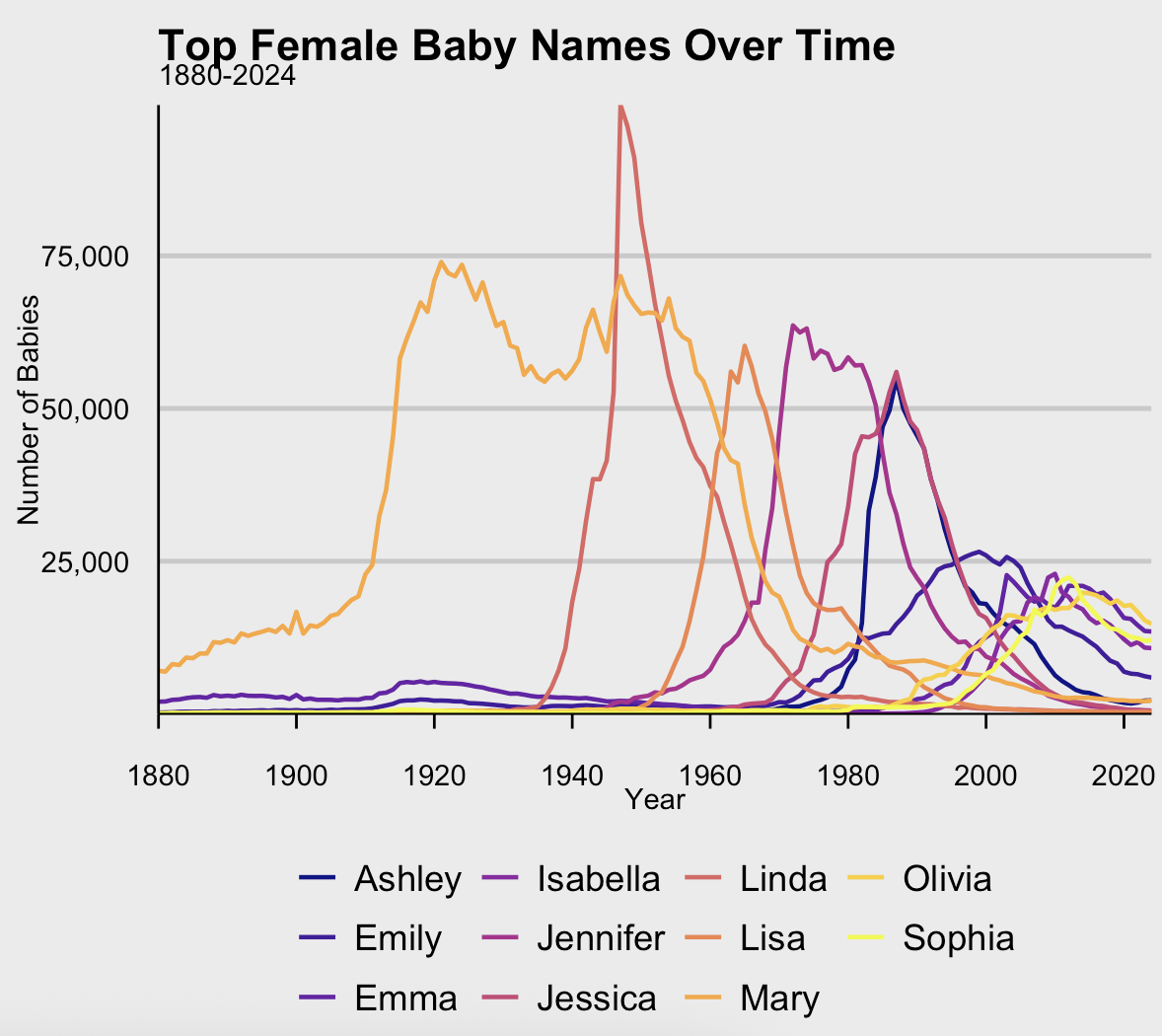

Nowadays, there is much more competition in names with less singular dominance and more of an oligopoly. While Olivia has taken the top spot for the past six years, it has been by a very narrow margin. There is one name in the top ten for 2024 that I would put my money on taking gold 🏅 this year: Amelia. And no, that is not just because my beautiful wife is named Amelia. The trajectory of the top ten names is paled in comparison with the name Amelia over the past two decades, and last year in particular.

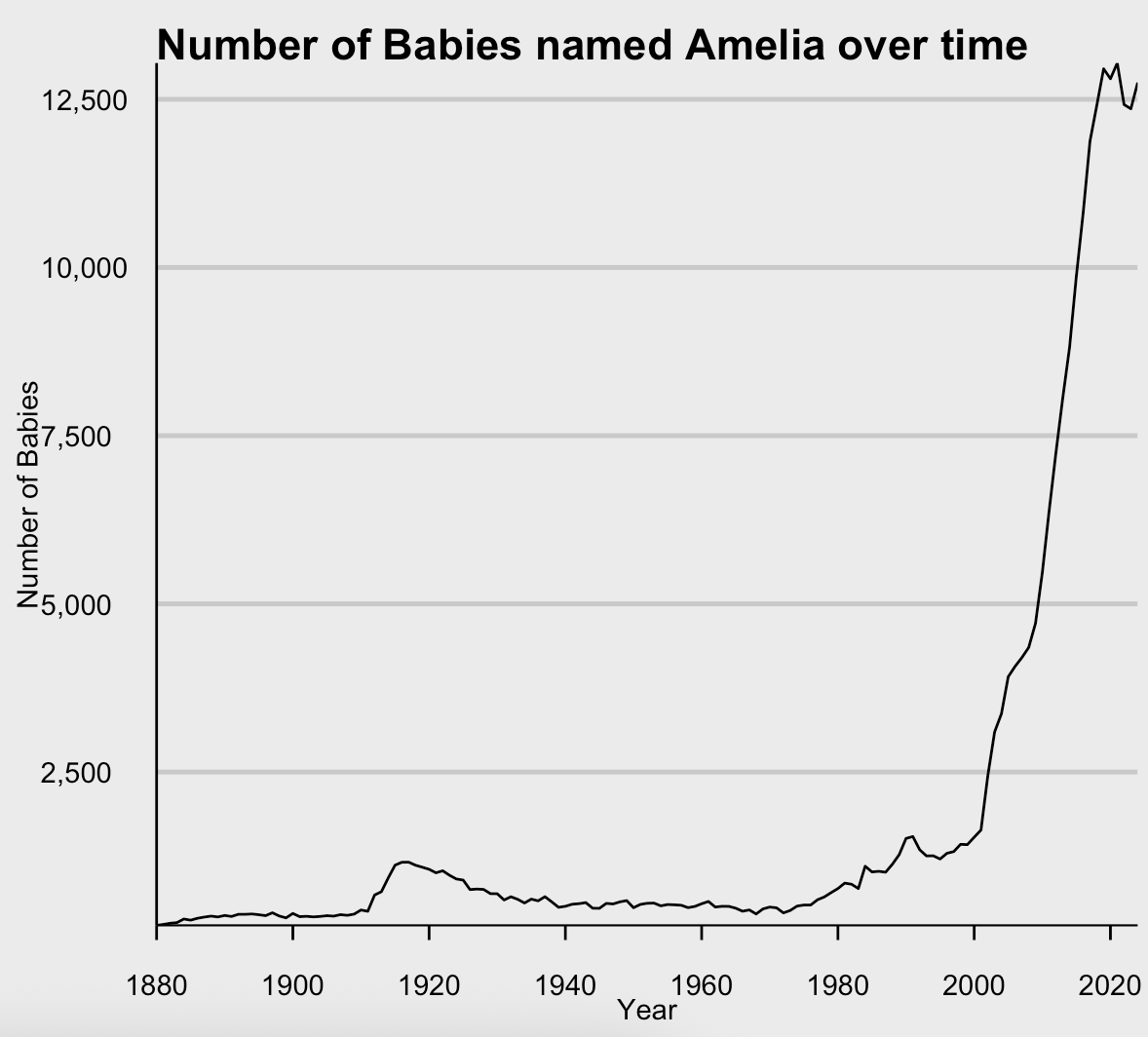

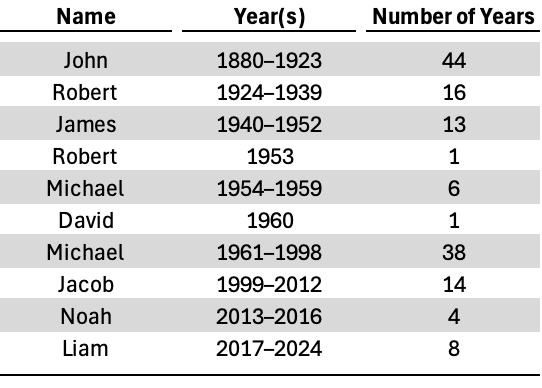

Men

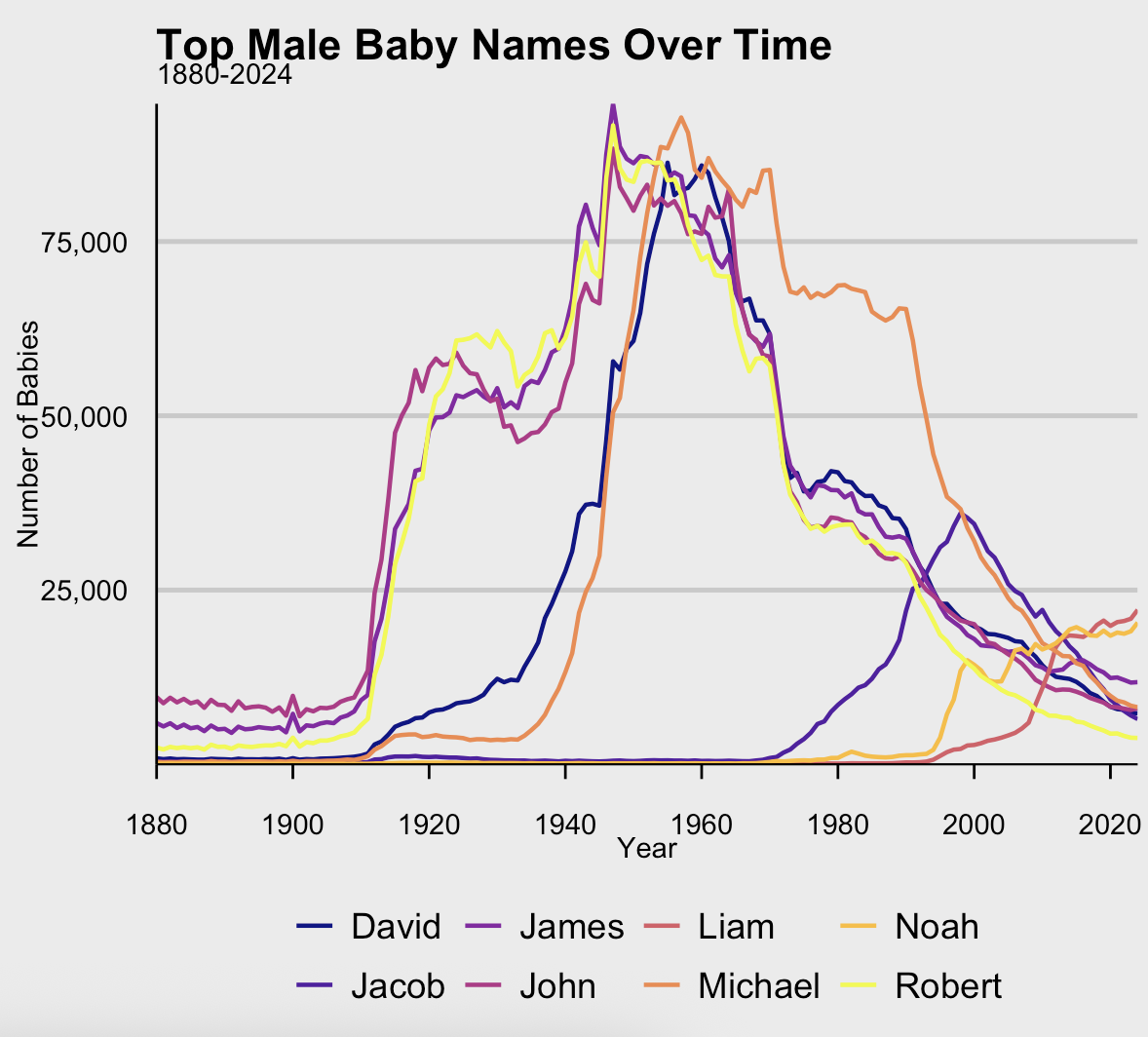

When we narrow in on baby boys, the number of top names over time is even smaller than the women, coming in at eight distinct names from the 144 years of available Census Data.

Without beating a dead horse, I do want to point out that a name with deep religious ties in Christianity—John—was the most popular name when the United States was, well, more religious. However, I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out that John did not have a dominant lead over other the names Robert and James for the first half of the 20th century.

The chart below makes it clear that there is more concentration of traditional names for baby boys when compared to baby girls. John, Robert, James, David, and Michael were all extremely popular names through the 1980s, and still are to this day to some extent. There are less spikes here for us to infer any acute cultural influences on how American parents name their children, but the same trend over the past twenty years shows in the boy names as the girl names: the share of babies with one name has significantly decreased.

Are we becoming more creative or just more diverse?

I want to note that it is actually impossible for us to answer the question I just posed, however it is an interesting one to ponder. Anecdotally speaking, I have been meeting way more young adults who have names that I have never seen before. I just read an article questioning whether Americans are getting less weird. All of the data points to “yes,” although our children’s’ names may object.

Historically, we have wanted to conform to society. We used to live in a word where men would go out to work on an assembly line from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. and women would stay at home to raise the family. On weekends, the family would go to church, maybe go to a baseball game or the cinema. The American Dream is much more of a gray area now. It is not just having the husband as the breadwinner, the wife as the caretaker, and buying a house with a white-picket fence.

While I do think many American adults want their child to be unique, I still think there is a form of conformity transpiring. In the world of social media, we see so many different walks of life and the algorithm will cater to your specific personality. Never has it been so easy to connect with like-minded individuals, which is obviously a good thing (in most scenarios), but you are also being convinced that that is the norm.

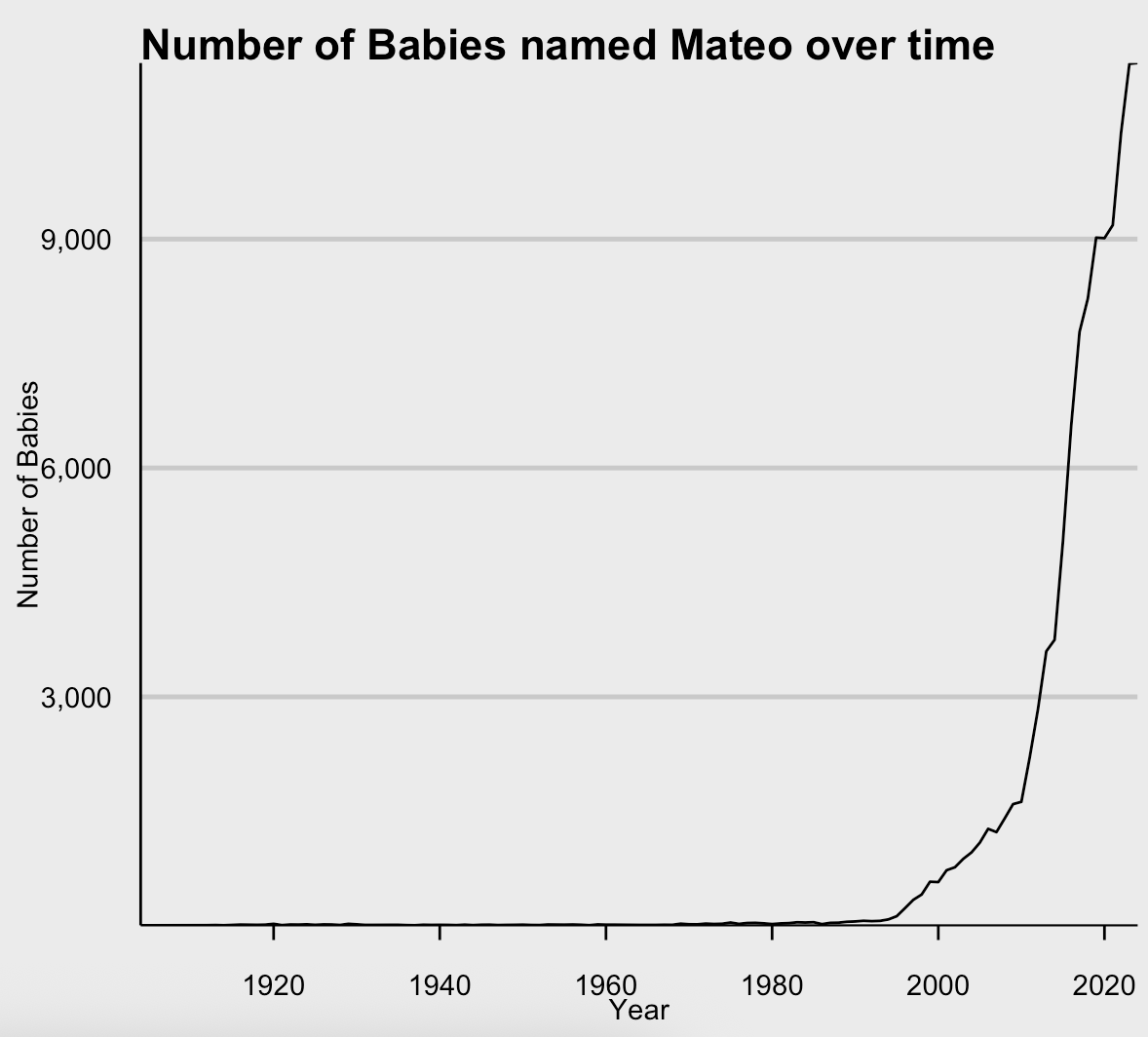

Of course, the United States is composed of many more immigrants than in the early 20th century and that cannot be overlooked in terms of the diversity of our names. In fact, the name “Mateo,” which is simply the name Matthew in Spanish and Italian, was the seventh most popular name for boys in 2024.

Ultimately, I don’t think we’ll ever be able to attribute, scientifically, what collectively determines a baby’s name. Though, it is clear that there is a desire to conform for most American adults. The conformity is just happening with many different subsets of society compared to the one “American Dream” that existed throughout most of the 20th century. This is largely fueled by immigration to our country, and the affirmation of your beliefs made possible by Big Tech. I don’t know what the most popular names will be in the future but what I would bet on is that there will never be one name as prevalent as we saw in the first half of the 1900s.

You can find all of the code for this blog post on my GitHub here.